Background

Overview

Teaching: 5 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

What is the Ocean Tracking Network?

How does your local telemetry network interact with OTN?

What methods of data analysis will be covered?

Objectives

Intro to OTN

The Ocean Tracking Network (OTN) supports global telemetry research by providing training, equipment, and data infrastructure to our large network of partners.

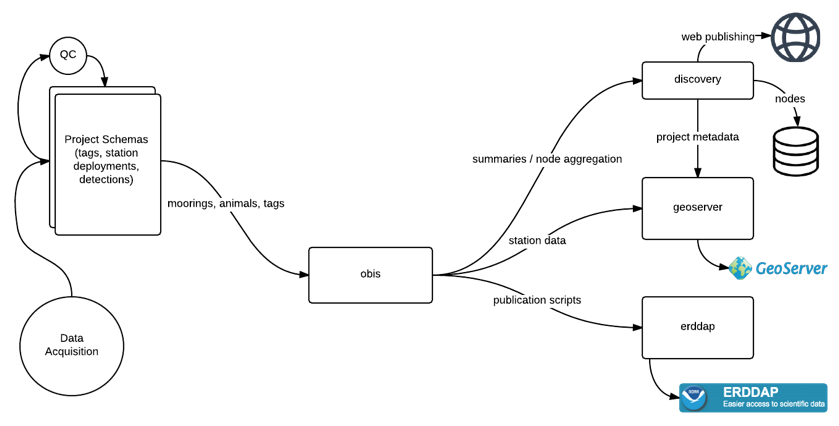

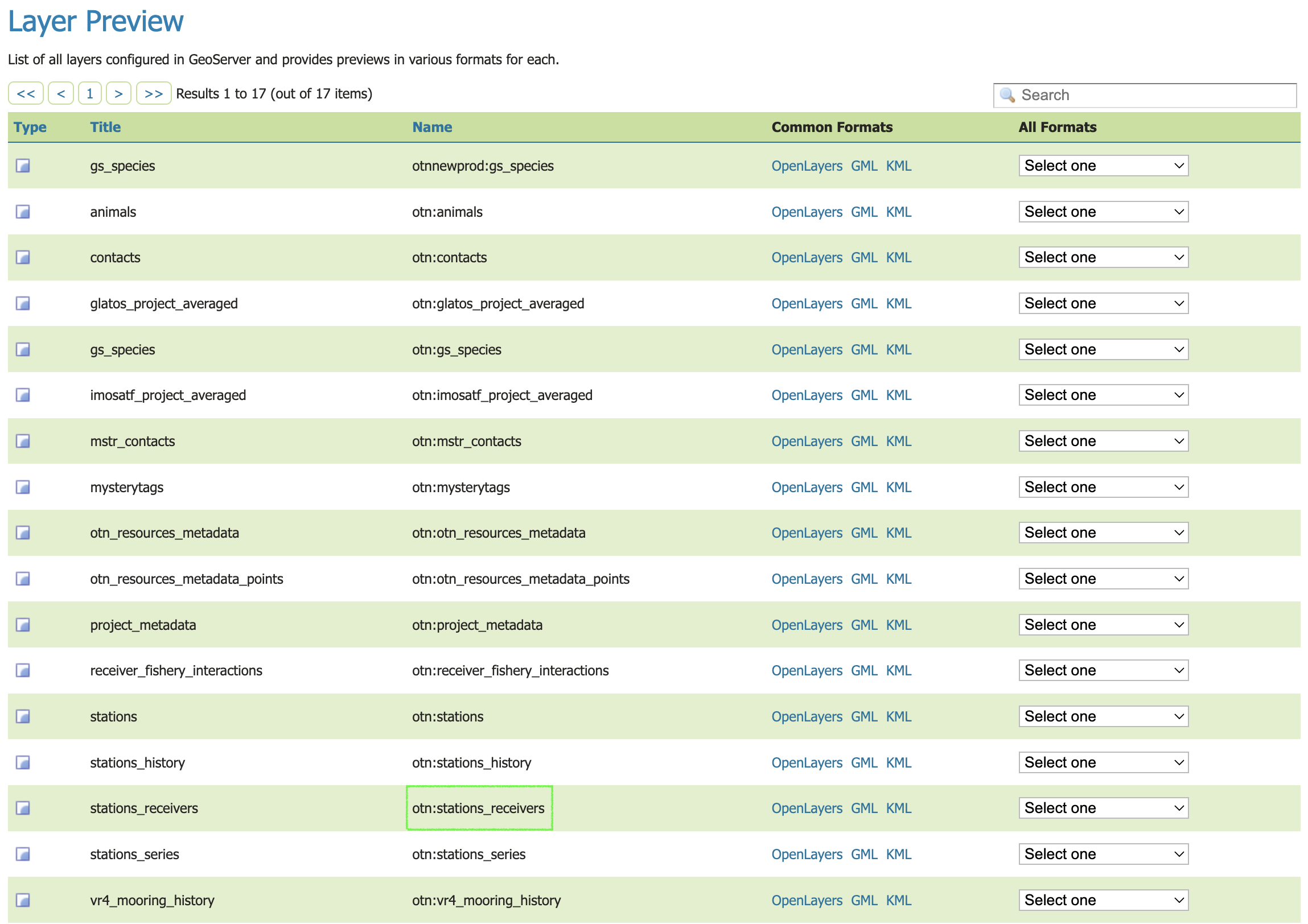

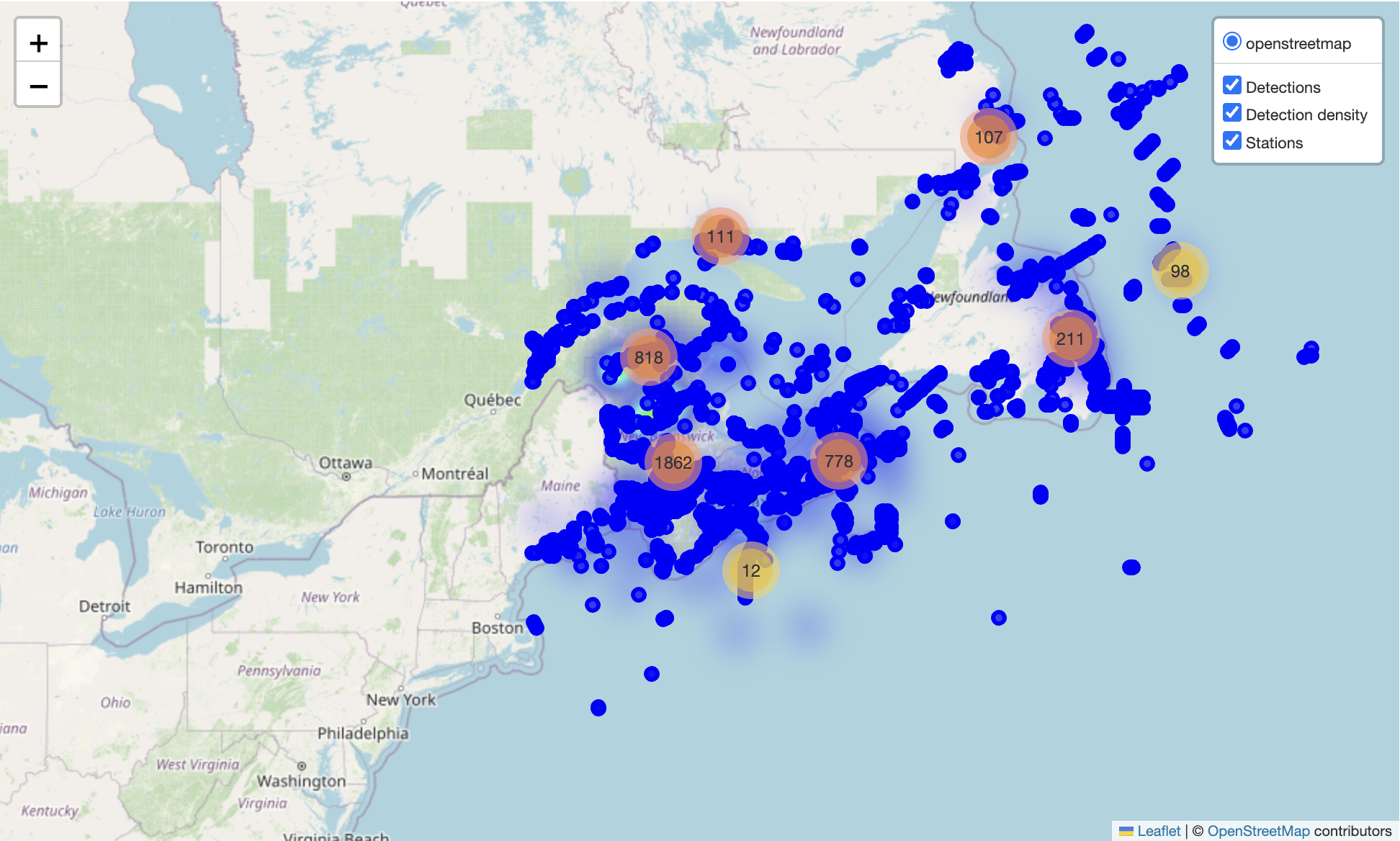

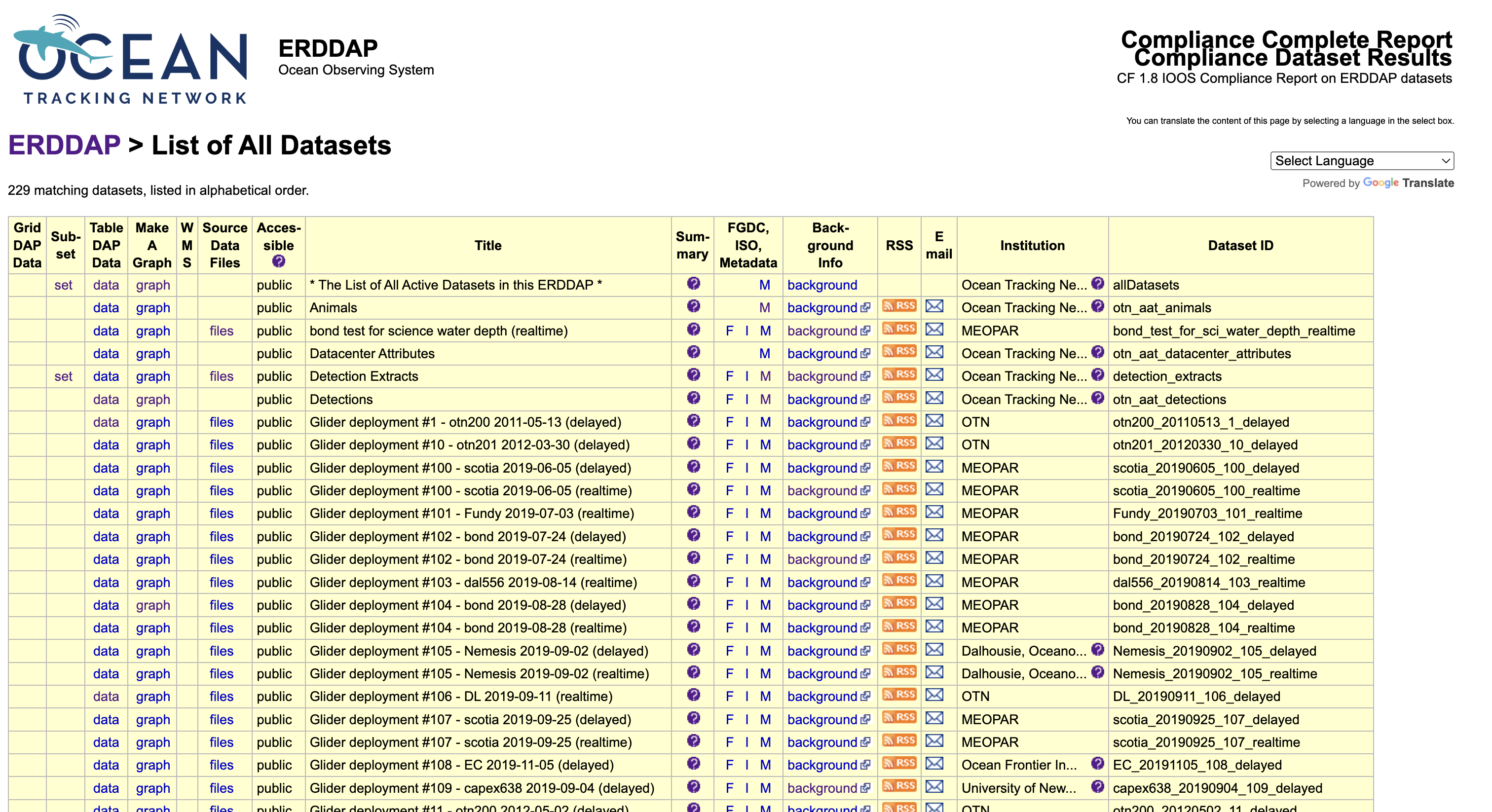

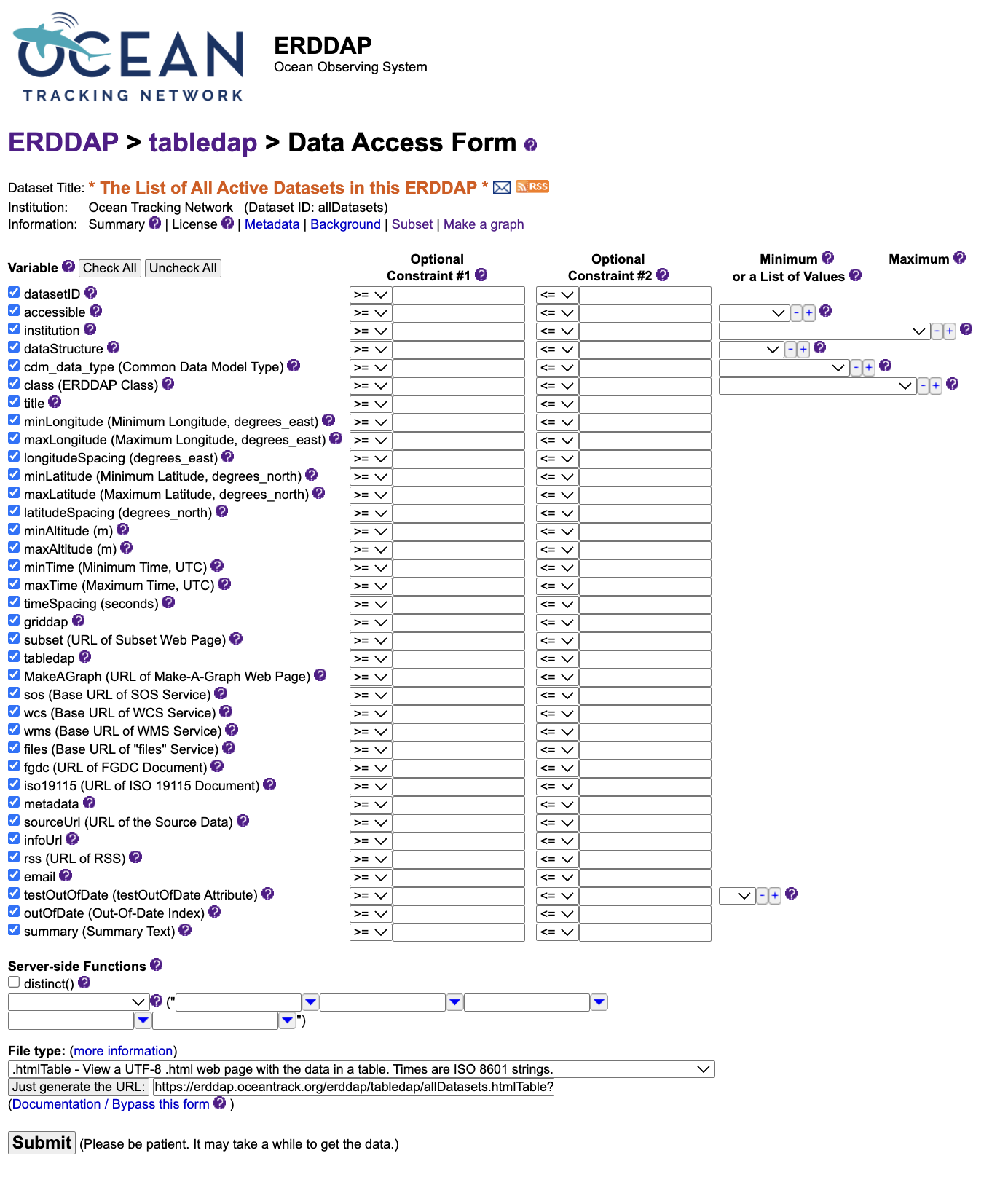

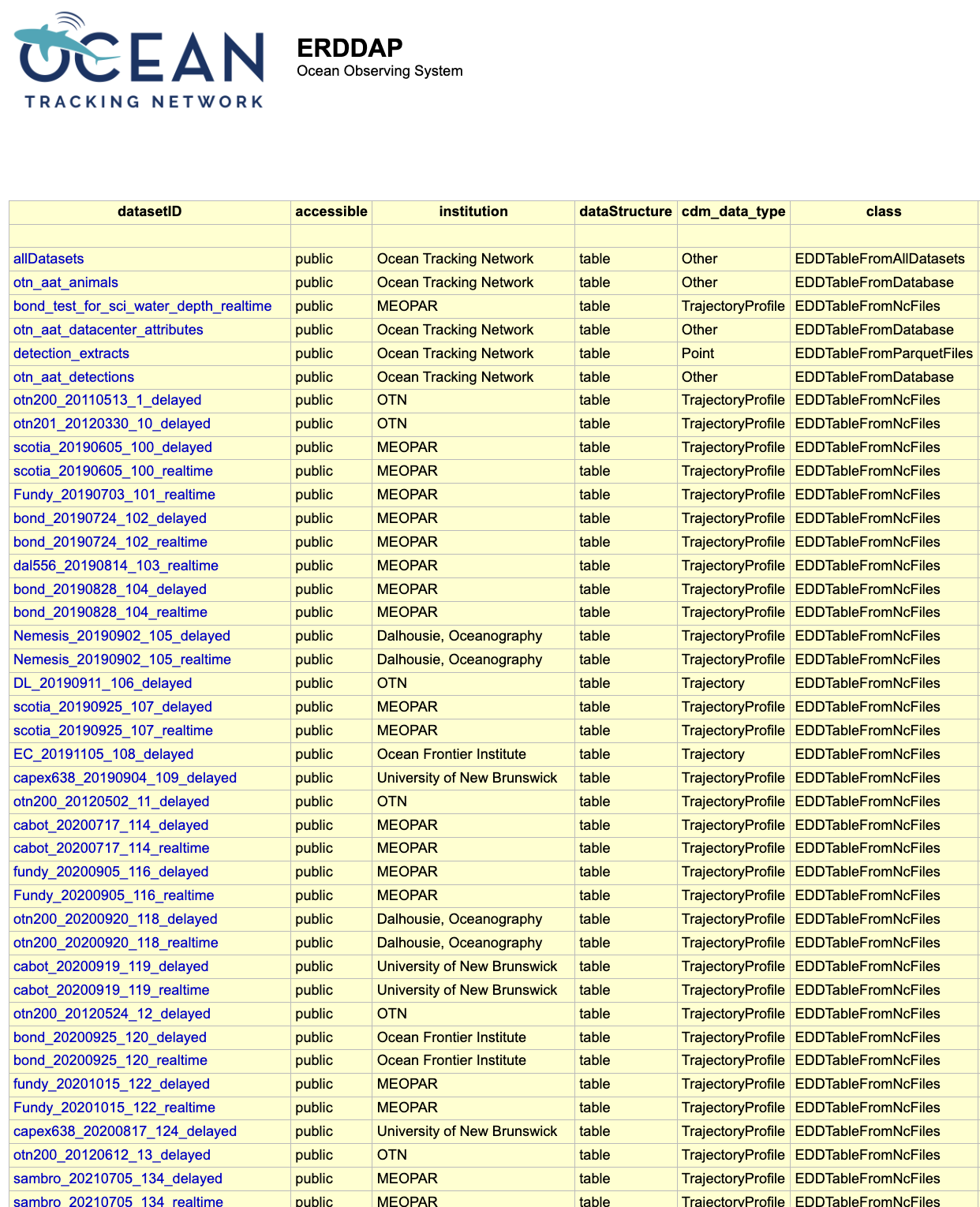

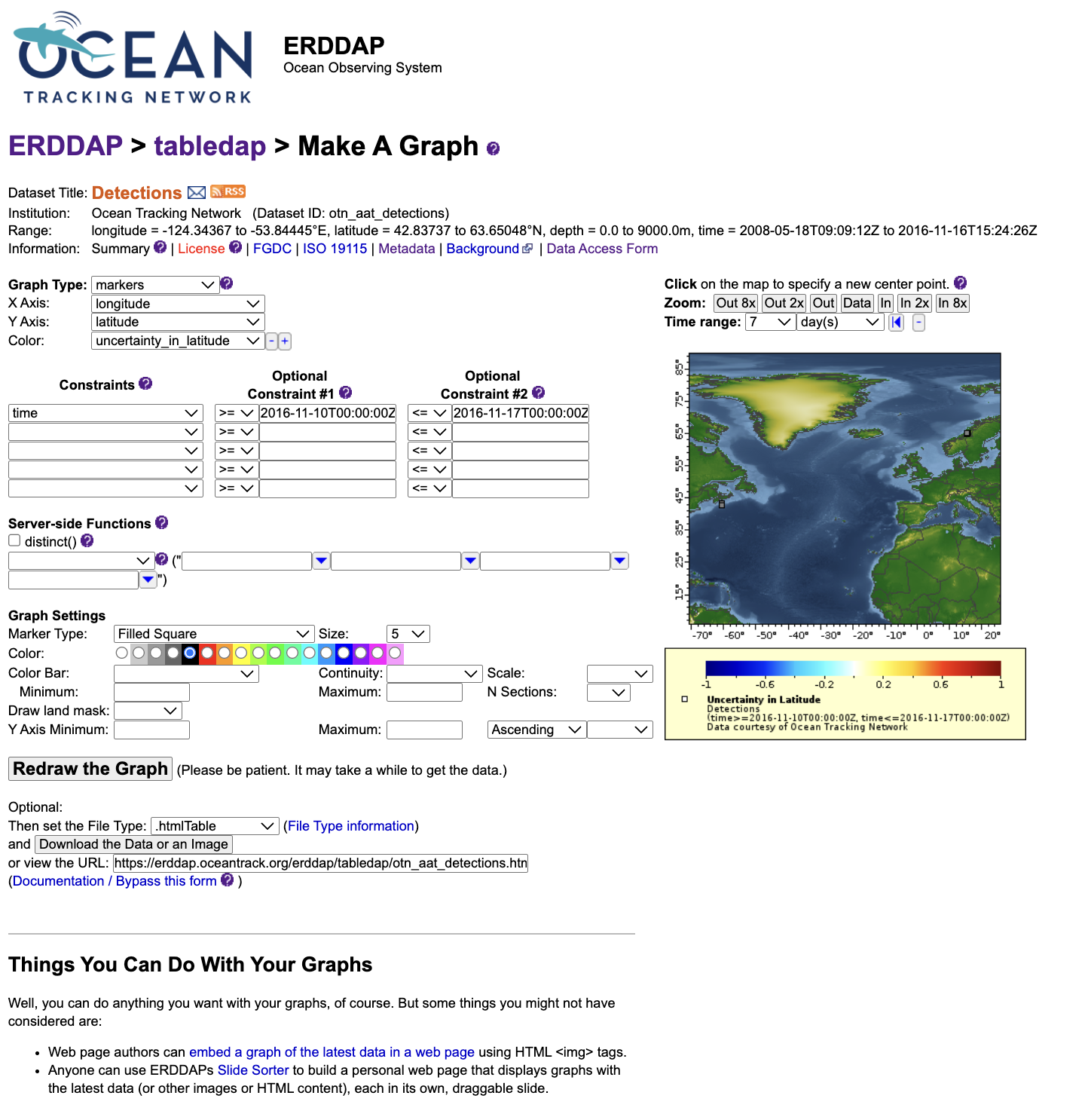

OTN and affiliated networks provide automated cross-referencing of your detection data with other tags in the system to help resolve “mystery detections” and provide detection data to taggers in other regions. OTN’s Data Managers will also extensively quality-control your submitted metadata for errors to ensure the most accurate records possible are stored in the database. OTN’s database and Data Portal website are excellent places to archive your datasets for future use and sharing with collaborators. We offer pathways to publish your datasets with OBIS, and via open data portals like ERDDAP, GeoServer etc. The data-product format returned by OTN is directly ingestible by analysis packages such as glatos and resonATe for ease of analysis. OTN offers support for the use of these packages and tools.

Learn more about OTN and our partners here https://members.oceantrack.org/. Please contact OTNDC@DAL.CA if you are interested in connecting with your regional network and learning about their affiliation with OTN.

Intended Audience

This set of workshop material is directed at researchers who are ready to begin the work of acoustic telemetry data analysis. The first few lessons will begin with introductory R - no previous coding experince required. The workshop material progresses into more advanced techniques as we move along, beginning around lesson 8 “Introduction to Glatos”.

If you’d like to refresh your R coding skills outside of this workshop curriculum, we recommend Data Analysis and Visualization in R for Ecologists as a good starting point. Much of this content is included in the first two lessons of this workshop.

Getting Started

Please follow the instrucions in the “Setup” tab along the top menu to install all required software, packages and data files. If you have questions or are running into errors please reach out to OTNDC@DAL.CA for support.

NOTE: this workshop has been update to align with OTN’s 2025 Detection Extract Format. For older detection extracts, please see the this lesson: Archived OTN Workshop.

Intro to Telemetry Data Analysis

OTN-affiliated telemetry networks all provide researchers with pre-formatted datasets, which are easily ingested into these data analysis tools.

Before diving in to a lot of analysis, it is important to take the time to clean and sort your dataset, taking the pre-formatted files and combining them in different ways, allowing you to analyse the data with different questions in mind.

There are multiple R packages necessary for efficient and thorough telemetry data analysis. General packages that allow for data cleaning and arrangement, dataset manipulation and visualization, pairing with oceanographic data and temporo-spatial locating are used in conjuction with the telemetry analysis tool packages remora, actel and glatos.

There are many more useful packages covered in this workshop, but here are some highlights:

Intro to the glatos Package

glatos is an R package with functions useful to members of the Great Lakes Acoustic Telemetry Observation System (http://glatos.glos.us). Developed by Chris Holbrook of GLATOS, OTN helps to maintain and keep relevant. Functions may be generally useful for processing, analyzing, simulating, and visualizing acoustic telemetry data, but are not strictly limited to acoustic telemetry applications. Tools included in this package facilitate false filtering of detections due to time between pings and disstance between pings. There are tools to summarise and plot, including mapping of animal movement. Learn more here.

Maintainer: Dr. Chris Holbrook, ( cholbrook@usgs.gov )

Intro to the actel Package

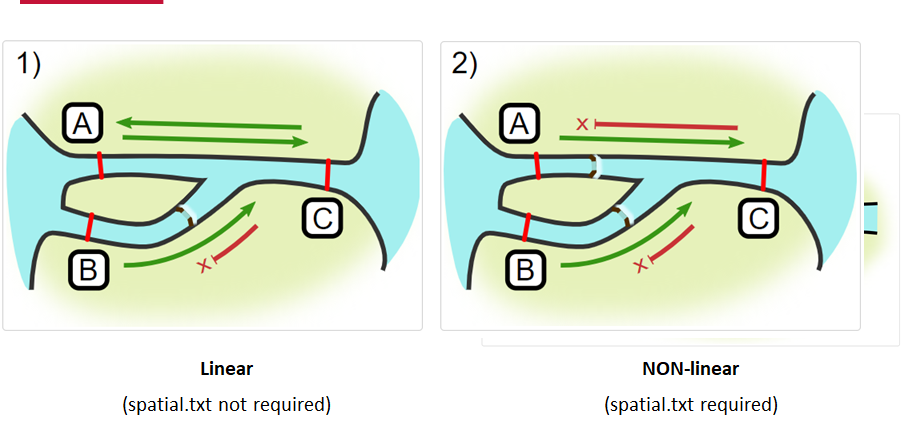

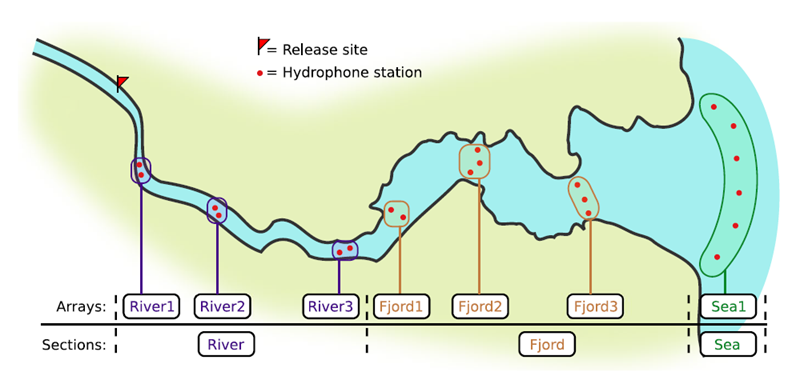

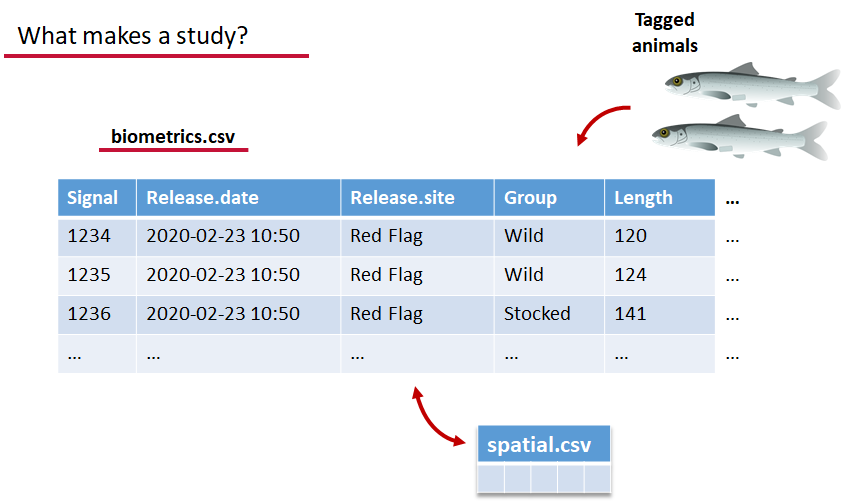

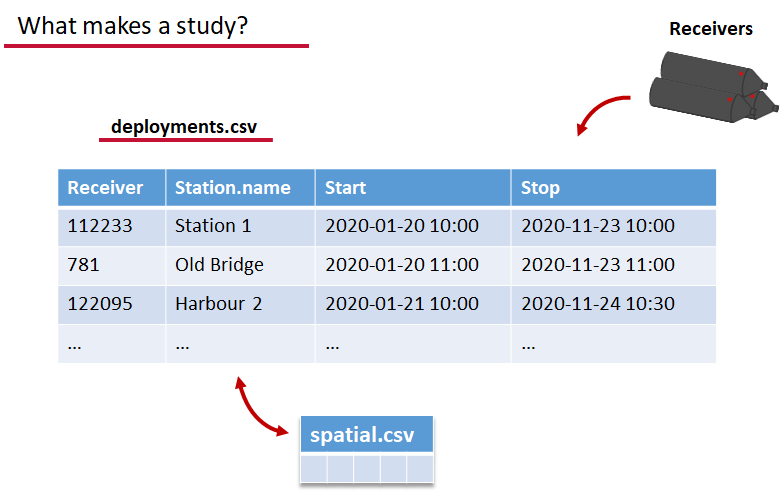

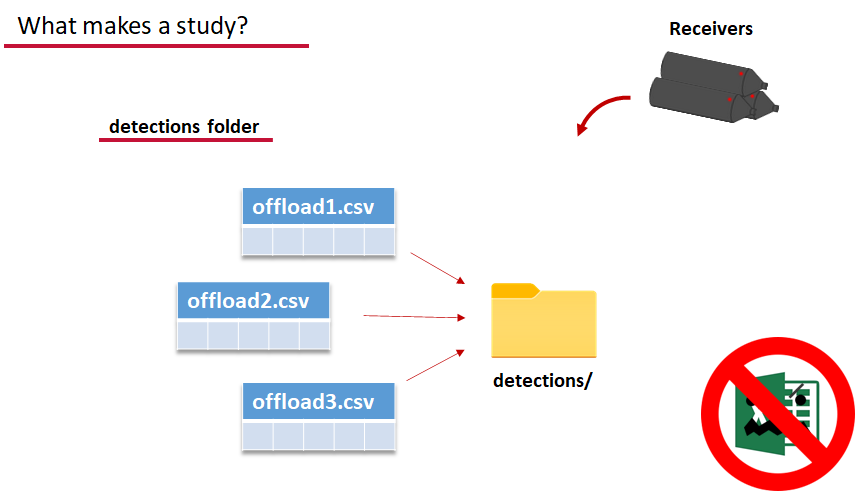

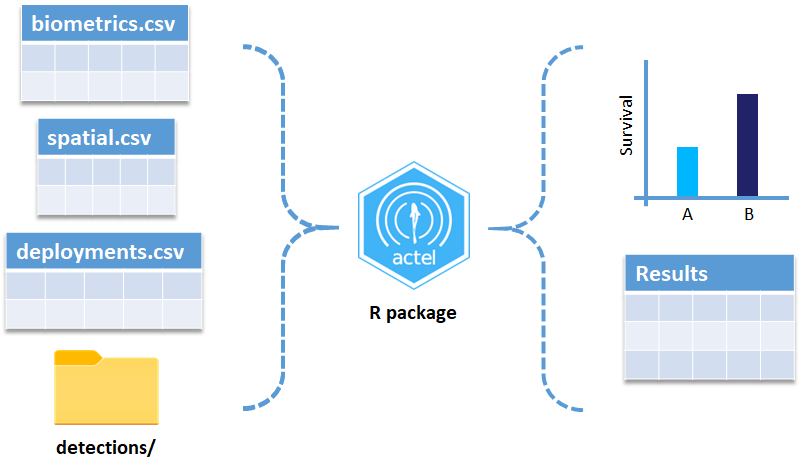

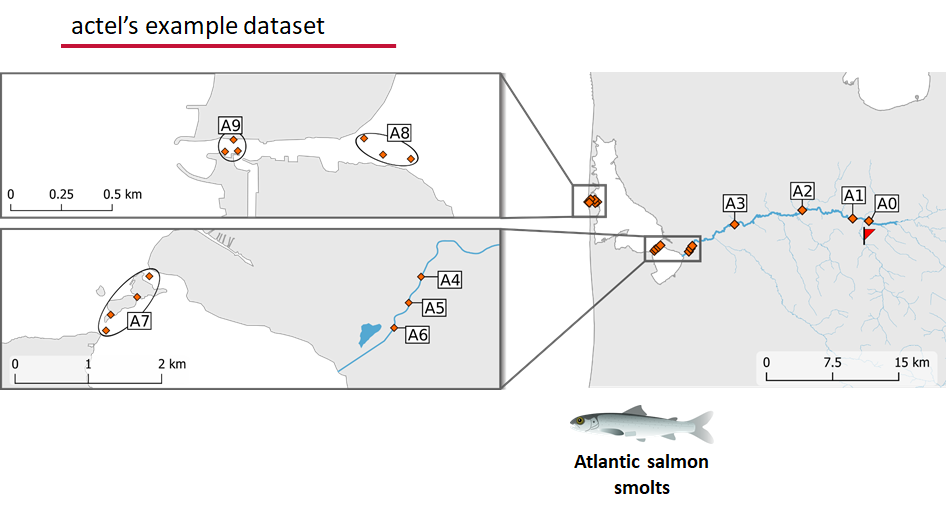

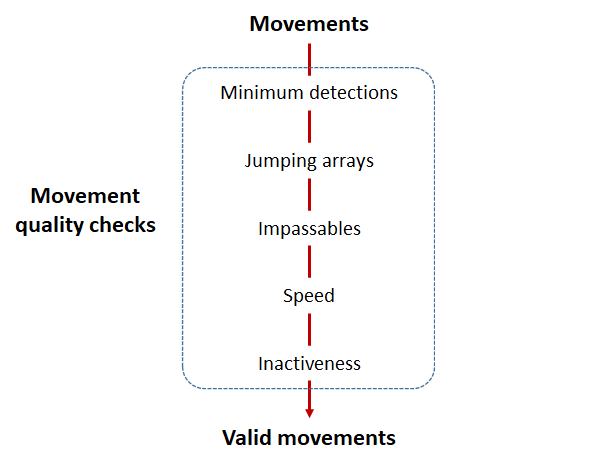

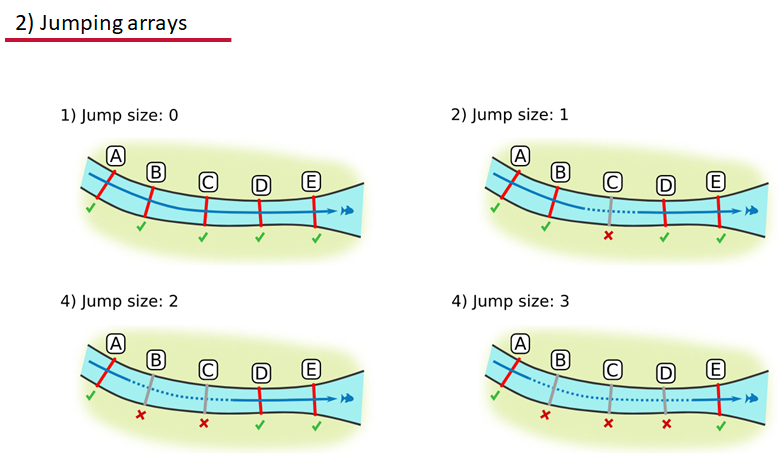

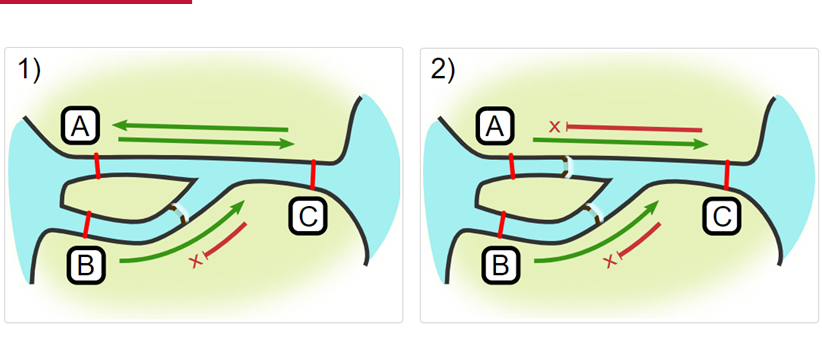

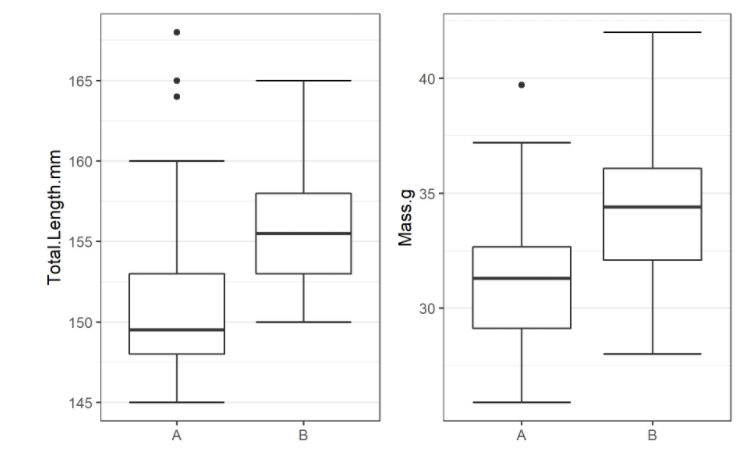

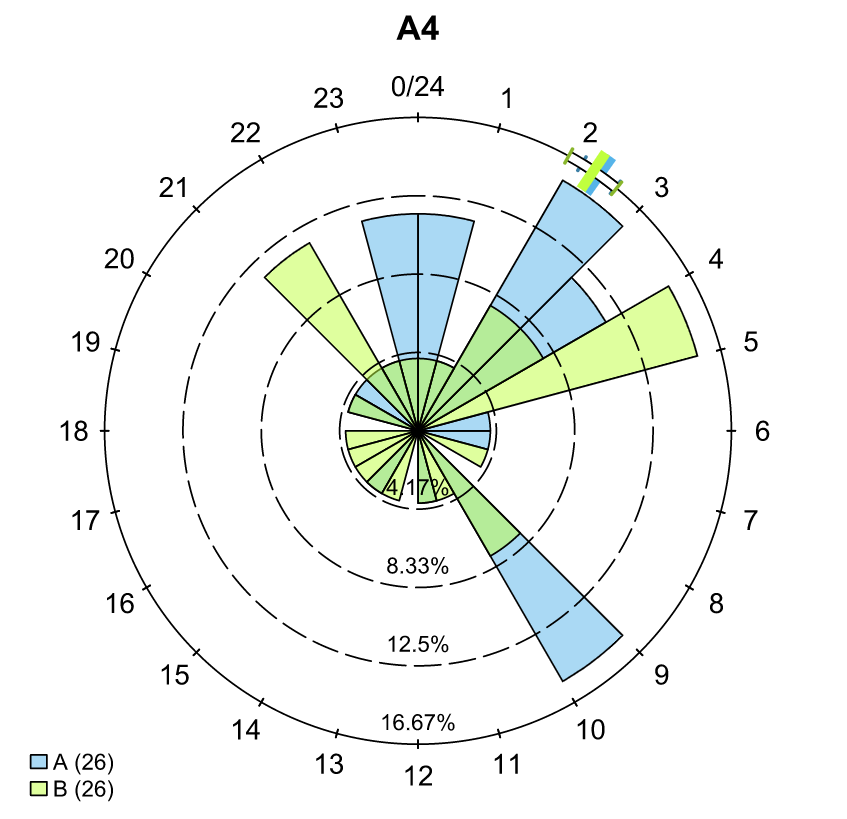

This package is designed for studies where animals tagged with acoustic tags are expected to move through receiver arrays. actel combines the advantages of automatic sorting and checking of animal movements with the possibility for user intervention on tags that deviate from expected behaviour. The three analysis functions: explore, migration and residency, allow the users to analyse their data in a systematic way, making it easy to compare results from different studies.

Author: Dr. Hugo Flavio, ( hflavio@wlu.ca )

Intro to the remora Package

This package is designed for the Rapid Extraction of Marine Observations for Roving Animals (remora). This is an R package that enables the integration of animal acoustic telemetry data with oceanographic observations collected by ocean observing programs. It includes functions for:

- Interactively exploring animal movements in space and time from acoustic telemetry data

- Performing robust quality-control of acoustic telemetry data as described in Hoenner et al. 2018

- Identifying available satellite-derived and sub-surface in situ oceanographic datasets coincident and collocated with the animal movement data, based on regional Ocean Observing Systems

- Extracting and appending these environmental data to animal movement data

Whilst the functions in remora were primarily developed to work with acoustic telemetry data, the environmental data extraction and integration functionalities will work with other spatio-temporal ecological datasets (eg. satellite telemetry, species sightings records, fisheries catch records).

Maintainer: Created by a team from IMOS Animal Tracking Facility, adapted to work on OTN-formatted data by Bruce Delo ( bruce.delo@dal.ca )

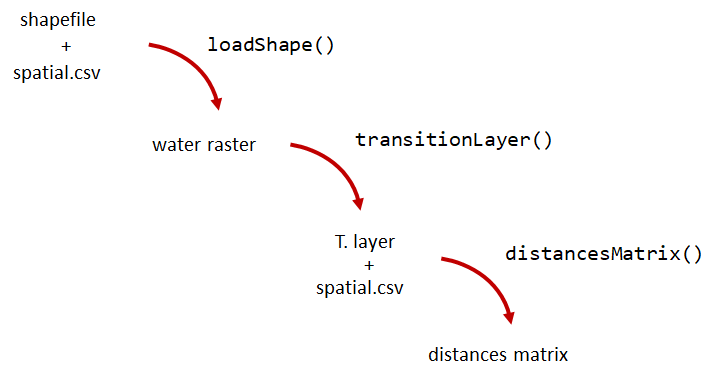

Intro to the pathroutr Package

The goal of pathroutr is to provide functions for re-routing paths that cross land around barrier polygons. The use-case in mind is movement paths derived from location estimates of marine animals. Due to error associated with these locations it is not uncommon for these tracks to cross land. The pathroutr package aims to provide a pragmatic and fast solution for re-routing these paths around land and along an efficient path. You can learn more here

Author: Dr. Josh M London ( josh.london@noaa.gov )

Key Points

Intro to R

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

What are common operators in R?

What are common data types in R?

What are some base R functions?

How do I deal with missing data?

Objectives

First, lets learn about RStudio.

RStudio is divided into 4 “Panes”: the Source for your scripts and documents (top-left, in the default layout); your Environment/History (top-right) which shows all the objects in your working space (Environment) and your command history (History); your Files/Plots/Packages/Help/Viewer (bottom-right); and the R Console (bottom-left). The placement of these panes and their content can be customized (see menu, Tools -> Global Options -> Pane Layout).

The R Script in the top pane can be saved and edited, while code typed directly into the Console below will disappear after closing the R session.

R can access files on and save outputs to any folder on your computer. R knows where to look for and save files based on the current working directory. This is one of the first things you should set up: a folder you’d like to contain all your data, scripts and outputs. The working directory path will be different for everyone. For the workshop, we’ve included the path one of our instructors uses, but you should use your computer’s file explorer to find the correct path for your data.

Setting up R

# Packages ####

# once you install packages to your computer, you can "check them out" of your packages library each time you need them

# make sure you check the "mask" messages that appear - sometimes packages have functions with the same names!

library(tidyverse)# really neat collection of packages! https://www.tidyverse.org/

library(lubridate)

library(readxl)

library(viridis)

library(plotly)

library(ggmap)

# Working Directory ####

#Instructors!! since this lesson is mostly base R we're not going to make four copies of it as with the other nodes.

#Change this one line as befits your audience.

setwd('YOUR/PATH/TO/data/NODE') #set folder you're going to work in

getwd() #check working directory

#you can also change it in the RStudio interface by navigating in the file browser where your working directory should be

#(if you can't see the folder you want, choose the three horizonal dots on the right side of the Home bar),

#and clicking on the blue gear icon "More", and select "Set As Working Directory".

Before we begin the lesson proper, a note on finding additional help. R Libraries, like those included above, are broad and contain many functions. Though most include documentation that can help if you know what to look for, sometimes more general help is necessary. To that end, RStudio maintains cheatsheets for several of the most popular libraries, which can be found here: https://www.rstudio.com/resources/cheatsheets/. As a start, the page includes an RStudio IDE cheatsheet that you may find useful while learning to navigate your workspace. With that in mind, let’s start learning R.

Intro to R

Like most programming langauges, we can do basic mathematical operations with R. These, along with variable assignment, form the basis of everything for which we will use R.

Operators

Operators in R include standard mathematical operators (+, -, *, /) as well as an assignment operator, <- (a less-than sign followed by a hyphen). The assignment operator is used to associate a value with a variable name (or, to ‘assign’ the value a name). This lets us refer to that value later, by the name we’ve given to it. This may look unfamiliar, but it fulfils the same function as the ‘=’ operator in most other languages.

3 + 5 #maths! including - , *, /

weight_kg <- 55 #assignment operator! for objects/variables. shortcut: alt + -

weight_kg

weight_lb <- 2.2 * weight_kg #can assign output to an object. can use objects to do calculations

Variables Challenge

If we change the value of weight_kg to be 100, does the value of weight_lb also change? Remember: You can check the contents of an object by typing out its name and running the line in RStudio.

Solution

No! You have to re-assign 2.2*weight_kg to the object weight_lb for it to update.

The order you run your operations is very important, if you change something you may need to re-run everything!

weight_kg <- 100 weight_lb #didnt change! weight_lb <- 2.2 * weight_kg #now its updated

Functions

While we can write code as we have in the section above - line by line, executed one line at a time - it is often more efficient to run multiple lines of code at once. By using functions, we can even compress complex calculations into just one line!

Functions use a single name to refer to underlying blocks of code that execute a specific calculation. To run a function you need two things: the name of the function, which is usually indicative of the function’s purpose; and the function’s arguments- the variables or values on which the function should execute.

#functions take "arguments": you have to tell them what to run their script against

ten <- sqrt(weight_kg) #contain calculations wrapped into one command to type.

#Output of the function can be assigned directly to a variable...

round(3.14159) #... but doesn't have to be.

Since there are hundreds of functions and often their functionality can be nuanced, we have several ways to get more information on a given function. First, we can use ‘args()’, itself a function that takes the name of another function as an argument, which will tell us the required arguments of the function against which we run it.

Second, we can use the ‘?’ operator. Typing a question mark followed by the name of a function will open a Help window in RStudio’s bottom-right panel. This will contain the most complete documentation available for the function in question.

args(round) #the args() function will show you the required arguments of another function

?round #will show you the full help page for a function, so you can see what it does

Functions Challenge

Can you round the value 3.14159 to two decimal places?

Hint: Using args() on a function can give you a clue.

Solution

round(3.14159, 2) #the round function's second argument is the number of digits you want in the result round(3.14159, digits = 2) #same as above round(digits = 2, x = 3.14159) #when reordered you need to specify

Vectors and Data Types

While variables can hold a single value, sometimes we want to store multiple values in the same variable name. For this, we can use an R data structure called a ‘vector.’ Vectors contain one or more variables of the same data type, and can be assigned to a single variable name, as below.

weight_g <- c(21, 34, 39, 54, 55) #use the combine function to join values into a vector object

length(weight_g) #explore vector

class(weight_g) #a vector can only contain one data type

str(weight_g) #find the structure of your object.

Above, we mentioned ‘data type’. This refers to the kind of data represented by a value, or stored by the appropriate variable. Data types include character (words or letters), logical (boolean TRUE or FALSE values), or numeric data. Crucially, vectors can only contain one type of data, and will force all data in the vector to conform to that type (i.e, data in the vector will all be treated as the same data type, regardless of whether or not it was of that type when the vector was created.) We can always check the data type of a variable or vector by using the ‘class()’ function, which takes the variable name as an argument.

#our first vector is numeric.

#other options include: character (words), logical (TRUE or FALSE), integer etc.

animals <- c("mouse", "rat", "dog") #to create a character vector, use quotes

class(weight_g)

class(animals)

# Note:

#R will convert (force) all values in a vector to the same data type.

#for this reason: try to keep one data type in each vector

#a data table / data frame is just multiple vectors (columns)

#this is helpful to remember when setting up your field sheets!

Vectors Challenge

What data type will this vector become?

challenge3 <- c(1, 2, 3, "4")Hint: You can check a vector’s type with the class() function.

Solution

R will force all of these to be characters, since the number 4 has quotes around it! Will always coerce data types following this structure: logical → numeric → character ← logical

class(challenge3)

Indexing and Subsetting

We can use subsetting to select only a portion of a vector. For this, we use square brackets after the name of a vector. If we supply a single numeric value, as below, we will retrieve only the value from that index of the vector. Note: vectors in R are indexed with 1 representing the first index- other languages use 0 for the start of their array, so if you are coming from a language like Python, this can be disorienting.

animals #calling your object will print it out

animals[2] #square brackets = indexing. selects the 2nd value in your vector

We can select a specific value, as above, but we can also select one or more entries based on conditions. By supplying one or more criteria to our indexing syntax, we can retrieve the elements of the array that match that criteria.

weight_g > 50 #conditional indexing: selects based on criteria

weight_g[weight_g <=30 | weight_g == 55] #many new operators here!

#<= less than or equal to; | "or"; == equal to. Also available are >=, greater than or equal to; < and > for less than or greater than (no equals); and & for "and".

weight_g[weight_g >= 30 & weight_g == 21] # >= greater than or equal to, & "and"

# this particular example give 0 results - why?

Missing Data

In practical data analysis, our data is often incomplete. It is therefore useful to cover some methods of dealing with NA values. NA is R’s shorthand for a null value; or a value where there is no data. Certain functions cannot process NA data, and therefore provide arguments that allow NA values to be removed before the function execution.

heights <- c(2, 4, 4, NA, 6)

mean(heights) #some functions cant handle NAs

mean(heights, na.rm = TRUE) #remove the NAs before calculating

This can be done within an individual function as above, but for our entire analysis we may want to produce a copy of our dataset without the NA values included. Below, we’ll explore a few ways to do that.

heights[!is.na(heights)] #select for values where its NOT NA

#[] square brackets are the base R way to select a subset of data --> called indexing

#! is an operator that reverses the function

na.omit(heights) #omit the NAs

heights[complete.cases(heights)] #select only complete cases

Missing Data Challenge

Question 1: Using the following vector of heighs in inches, create a new vector, called heights_no_na, with the NAs removed.

heights <- c(63, 69, 60, 65, NA, 68, 61, 70, 61, 59, 64, 69, 63, 63, NA, 72, 65, 64, 70, 63, 65)Solution

heights_no_na <- heights[!is.na(heights)] # or heights_no_na <- na.omit(heights) # or heights_no_na <- heights[complete.cases(heights)]Question 2: Use the function median() to calculate the median of the heights vector.

Solution

median(heights, na.rm = TRUE)Bonus question: Use R to figure out how many people in the set are taller than 67 inches.

Solution

heights_above_67 <- heights_no_na[heights_no_na > 67] length(heights_above_67)

Key Points

Starting with Data Frames

Overview

Teaching: 25 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

How do I import tabular data?

How do I explore my data set?

What are some basic data manipulation functions?

Objectives

NOTE: this workshop has been update to align with OTN’s 2025 Detection Extract Format. For older detection extracts, please see the this lesson: Archived OTN Workshop.

Note to instructors: please choose the relevant Network below when teaching

ACT Node

Dataframes and dplyr

In this lesson, we’re going to introduce a package called dplyr. dplyr takes advantage of an operator called a pipe to create chains of data manipulation that produce powerful exploratory summaries. It also provides a suite of further functionality for manipulating dataframes: tabular sets of data that are common in data analysis. If you’ve imported the tidyverse library, as we did during setup and in the last episode, then congratulations: you already have dplyr (along with a host of other useful packages). As an aside, the cheat sheets for dplyr and readr may be useful when reviewing this lesson.

You may not be familiar with dataframes by name, but you may recognize the structure. Dataframes are arranged into rows and columns, not unlike tables in typical spreadsheet format (ex: Excel). In R, they are represented as vectors of vectors: that is, a vector wherein each column is itself a vector. If you are familiar with matrices, or two-dimensional arrays in other languages, the structure of a dataframe will be clear to you.

However, dataframes are not merely vectors- they are a specific type of object with their own functionality, which we will cover in this lesson.

We are going to use OTN-style detection extracts for this lesson. If you’re unfamiliar with detection extracts formats from OTN-style database nodes, see the documentation here

Importing from CSVs

Before we can start analyzing our data, we need to import it into R. Fortunately, we have a function for this. read_csv is a function from the readr package, also included with the tidyverse library. This function can read data from a .csv file into a dataframe. “.csv” is an extension that denotes a Comma-Separated Value file, or a file wherein data is arranged into rows, and entries within rows are delimited by commas. They’re common in data analysis.

For the purposes of this lesson, we will only cover read_csv; however, there is another function, read_excel, which you can use to import excel files. It’s from a different library (readxl) and is outside the scope of this lesson, but worth investigating if you need it.

To import your data from your CSV file, we just need to pass the file path to read_csv, and assign the output to a variable. Note that the file path you give to read_csv will be relative to the working directory you set in the last lesson, so keep that in mind.

#imports file into R. paste the filepath to the file here!

#read_csv can take both csv and zip files, as long as the zip file contains a csv.

cbcnr_matched_2016 <- read_csv("cbcnr_matched_detections_2016.zip")

Regarding Parquet Files

OTN now sends out detection extracts in

.parquetformat rather than only.csv. Full documentation on the parquet file format can be found here, but in brief, it is an alternative to other tabular data formats that is designed for more efficient data storage and retrieval. If you have a parquet file, you will need to import it usingread_parquetfrom thenanoparquetpackage rather thanread_csv, like so:cbcnr_matched_2016 <- read_parquet("cbcnr_matched_detections_2016.parquet")Replace the filename with the appropriate path to your own parquet file. Everything hereafter will work the same:

read_parquetimports the data as a dataframe, and the column names and data types are identical across the CSV and Parquet versions of the detection extract. That means once the data is imported into R, the rest of the code in the workshop will work identically on it.

We can now refer to the variable cbcnr_matched_2016 to access, manipulate, and view the data from our CSV. In the next sections, we will explore some of the basic operations you can perform on dataframes.

Exploring Detection Extracts

Let’s start with a practical example. What can we find out about these matched detections? We’ll begin by running the code below, and then give some insight into what each function does. Remember, if you’re ever confused about the purpose of a function, you can use ‘?’ followed by the function name (i.e, ?head, ?View) to get more information.

head(cbcnr_matched_2016) #first 6 rows

View(cbcnr_matched_2016) #can also click on object in Environment window

str(cbcnr_matched_2016) #can see the type of each column (vector)

glimpse(cbcnr_matched_2016) #similar to str()

#summary() is a base R function that will spit out some quick stats about a vector (column)

#the $ syntax is the way base R selects columns from a data frame

summary(cbcnr_matched_2016$decimalLatitude)

You may now have an idea of what each of those functions does, but we will briefly explain each here.

head takes the dataframe as a parameter and returns the first 6 rows of the dataframe. This is useful if you want to quickly check that a dataframe imported, or that all the columns are there, or see other such at-a-glance information. Its primary utility is that it is much faster to load and review than the entire dataframe, which may be several tens of thousands of rows long. Note that the related function tail will return the last six elements.

If we do want to load the entire dataframe, though, we can use View, which will open the dataframe in its own panel, where we can scroll through it as though it were an Excel file. This is useful for seeking out specific information without having to consult the file itself. Note that for large dataframes, this function can take a long time to execute.

Next are the functions str and glimpse, which do similar but different things. str is short for ‘structure’ and will print out a lot of information about your dataframe, including the number of rows and columns (called ‘observations’ and ‘variables’), the column names, the first four entries of each column, and each column type as well. str can sometimes be a bit overwhelming, so if you want to see a more condensed output, glimpse can be useful. It prints less information, but is cleaner and more compact, which can be desirable.

Finally, we have the summary function, which takes a single column from a dataframe and produces a summary of its basic statistics. You may have noticed the ‘$’ in the summary call- this is how we index a specific column from a dataframe. In this case, we are referring to the latitude column of our dataframe.

Using what you now know about summary functions, try to answer the challenge below.

Detection Extracts Challenge

Question 1: What is the class of the station column in cbcnr_matched_2016, and how many rows and columns are in the cbcnr_matched_2016 dataset??

Solution

The column is a character, and there are 7,693 rows with 36 columns

str(cbcnr_matched_2016) # or glimpse(cbcnr_matched_2016)

Data Manipulation

Now that we’ve learned how to import and summarize our data, we can learn how to use dplyr to manipulate it. The name ‘dplyr’ may seem esoteric- the ‘d’ is short for ‘dataframe’, and ‘plyr’ is meant to evoke pliers, and thereby cutting, twisting, and shaping. This is an elegant summation of the dplyr library’s functionality.

We are going to introduce a new operator in this section, called the “dplyr pipe”. Not to be confused with |, which is also called a pipe in some other languages, the dplyr pipe is rendered as %>%. A pipe takes the output of the function or contents of the variable on the left and passes them to the function on the right. It is often read as “and then.” If you want to quickly add a pipe, the keybord shortcut CTRL + SHIFT + M will do so.

library(dplyr) #can use tidyverse package dplyr to do exploration on dataframes in a nicer way

# %>% is a "pipe" which allows you to join functions together in sequence.

cbcnr_matched_2016 %>% dplyr::select(6) #selects column 6

# Using the above transliteration: "take cbcnr_matched_2016 AND THEN select column number 6 from it using the select function in the dplyr library"

You may have noticed another unfamiliar operator above, the double colon (::). This is used to specify the package from which we want to pull a function. Until now, we haven’t needed this, but as your code grows and the number of libraries you’re using increases, it’s likely that multiple functions across several different packages will have the same name (a phenomenon called “overloading”). R has no automatic way of knowing which package contains the function you are referring to, so using double colons lets us specify it explicitly. It’s important to be able to do this, since different functions with the same name often do markedly different things.

Let’s explore a few other examples of how we can use dplyr and pipes to manipulate our dataframe.

cbcnr_matched_2016 %>% slice(1:5) #selects rows 1 to 5 in the dplyr way

# Take cbcnr_matched_2016 AND THEN slice rows 1 through 5.

#We can also use multiple pipes.

cbcnr_matched_2016 %>%

distinct(detectedBy) %>%

nrow #number of arrays that detected my fish in dplyr!

# Take cbcnr_matched_2016 AND THEN select only the unique entries in the detectedBy column AND THEN count them with nrow.

#We can do the same as above with other columns too.

cbcnr_matched_2016 %>%

distinct(catalogNumber) %>%

nrow #number of animals that were detected

# Take cbcnr_matched_2016 AND THEN select only the unique entries in the catalogNumber column AND THEN count them with nrow.

#We can use filtering to conditionally select rows as well.

cbcnr_matched_2016 %>% filter(catalogNumber=="CBCNR-1191602-2014-07-24")

# Take cbcnr_matched_2016 AND THEN select only those rows where catalogNumber is equal to the above value.

cbcnr_matched_2016 %>% filter(decimalLatitude >= 38) #all dets in/after October of 2016

# Take cbcnr_matched_2016 AND THEN select only those rows where latitude is greater than or equal to 38.

These are all ways to extract a specific subset of our data, but dplyr can also be used to manipulate dataframes to give you even greater insights. We’re now going to use two new functions: group_by, which allows us to group our data by the values of a single column, and summarise (not to be confused with summary above!), which can be used to calculate summary statistics across your grouped variables, and produces a new dataframe containing these values as the output. These functions can be difficult to grasp, so don’t forget to use ?group_by and ?summarise if you get lost.

#get the mean value across a column using GroupBy and Summarize

cbcnr_matched_2016 %>% #Take cbcnr_matched_2016, AND THEN...

group_by(catalogNumber) %>% #Group the data by catalogNumber- that is, create a group within the dataframe where each group contains all the rows related to a specific catalogNumber. AND THEN...

summarise(MeanLat=mean(decimalLatitude)) #use summarise to add a new column containing the mean decimalLatitude of each group. We named this new column "MeanLat" but you could name it anything

With just a few lines of code, we’ve created a dataframe that contains each of our catalog numbers and the mean latitude at which those fish were detected. dplyr, its wide array of functions, and the powerful pipe operator can let us build out detailed summaries like this one without writing too much code.

Data Manipulation Challenge

Question 1: Find the max lat and max longitude for animal “CBCNR-1191602-2014-07-24”.

Solution

cbcnr_matched_2016 %>% filter(catalogNumber=="CBCNR-1191602-2014-07-24") %>% summarise(MaxLat=max(decimalLatitude), MaxLong=max(decimalLongitude))Question 2: Find the min lat/long of each animal for detections occurring in June.

Solution

cbcnr_matched_2016 %>% filter(month(dateCollectedUTC) == 6) %>% group_by(catalogNumber) %>% summarise(MinLat=min(decimalLatitude), MinLong=min(decimalLongitude))

Joining Detection Extracts

We’re now going to briefly touch on a few useful dataframe use-cases that aren’t directly related to dplyr, but with which dplyr can help us.

One function that we’ll need to know is rbind, a base R function which lets us combine two R objects together. Since detections for animals tagged during a study often appear in multiple years, this functionality will let us merge the dataframes together. We’ll also use distinct, a dplyr function that lets us trim out duplicate release records for each animal, since these are listed in each detection extract.

cbcnr_matched_2017 <- read_csv("cbcnr_matched_detections_2017.zip") #First, read in our file.

cbcnr_matched_full <- rbind(cbcnr_matched_2016, cbcnr_matched_2017) #Now join the two dataframes

# release records for animals often appear in >1 year, this will remove the duplicates

cbcnr_matched_full <- cbcnr_matched_full %>% distinct() # Use distinct to remove duplicates.

View(cbcnr_matched_full)

Dealing with Datetimes

Datetime data is in a special format which is neither numeric nor character. It can be tricky to deal with, too, since Excel frequently reformats dates in any file it opens. We also have to concern ourselves with practical matters of time, like time zone and date formatting. Fortunately, the lubridate library gives us a whole host of functionality to manage datetime data. For additional help, the cheat sheet for lubridate may prove a useful resource.

We’ll also use a dplyr function called mutate, which lets us add new columns or change existing ones, while preserving the existing data in the table. Be careful not to confuse this with its sister function transmute, which adds or manipulates columns while dropping existing data. If you’re ever in doubt as to which is which, remember: ?mutate and ?transmute will bring up the help files.

library(lubridate) #Import our Lubridate library.

cbcnr_matched_full %>% mutate(dateCollectedUTC=ymd_hms(dateCollectedUTC)) #Use the lubridate function ymd_hms to change the format of the date.

#as.POSIXct(cbcnr_matched_full$dateCollectedUTC) #this is the base R way - if you ever see this function

We’ve just used a single function, ymd_hms, but with it we’ve been able to completely reformat the entire datecollectedUTC column. ymd_hms is short for Year, Month, Day, Hours, Minutes, and Seconds. For example, at time of writing, it’s 2021-05-14 14:21:40. Other format functions exist too, like dmy_hms, which specifies the day first and year third (i.e, 14-05-2021 14:21:40). Investigate the documentation to find which is right for you.

There are too many useful lubridate functions to cover in the scope of this lesson. These include parse_date_time, which can be used to read in date data in multiple formats, which is useful if you have a column contianing heterogenous date data; as well as with_tz, which lets you make your data sensitive to timezones (including automatic daylight savings time awareness). Dates are a tricky subject, so be sure to investigate lubridate to make sure you find the functions you need.

FACT Node

Dataframes and dplyr

In this lesson, we’re going to introduce a package called dplyr. dplyr takes advantage of an operator called a pipe to create chains of data manipulation that produce powerful exploratory summaries. It also provides a suite of further functionality for manipulating dataframes: tabular sets of data that are common in data analysis. If you’ve imported the tidyverse library, as we did during setup and in the last episode, then congratulations: you already have dplyr (along with a host of other useful packages). As an aside, the cheat sheets for dplyr and readr may be useful when reviewing this lesson.

You may not be familiar with dataframes by name, but you may recognize the structure. Dataframes are arranged into rows and columns, not unlike tables in typical spreadsheet format (ex: Excel). In R, they are represented as vectors of vectors: that is, a vector wherein each column is itself a vector. If you are familiar with matrices, or two-dimensional arrays in other languages, the structure of a dataframe will be clear to you.

However, dataframes are not merely vectors- they are a specific type of object with their own functionality, which we will cover in this lesson.

We are going to use OTN-style detection extracts for this lesson. If you’re unfamiliar with detection extracts formats from OTN-style database nodes, see the documentation here

Importing from CSVs

Before we can start analyzing our data, we need to import it into R. Fortunately, we have a function for this. read_csv is a function from the readr package, also included with the tidyverse library. This function can read data from a .csv file into a dataframe. “.csv” is an extension that denotes a Comma-Separated Value file, or a file wherein data is arranged into rows, and entries within rows are delimited by commas. They’re common in data analysis.

For the purposes of this lesson, we will only cover read_csv; however, there is another function, read_excel, which you can use to import excel files. It’s from a different library (readxl) and is outside the scope of this lesson, but worth investigating if you need it.

To import your data from your CSV file, we just need to pass the file path to read_csv, and assign the output to a variable. Note that the file path you give to read_csv will be relative to the working directory you set in the last lesson, so keep that in mind.

#imports file into R. paste the filepath to the unzipped file here!

#read_csv can take both csv and zip files, as long as the zip file contains a csv.

tqcs_matched_2010 <- read_csv("tqcs_matched_detections_2010.zip", guess_max = 117172) #Import 2010 detections

Regarding Parquet Files

OTN now sends out detection extracts in

.parquetformat rather than only.csv. Full documentation on the parquet file format can be found here, but in brief, it is an alternative to other tabular data formats that is designed for more efficient data storage and retrieval. If you have a parquet file, you will need to import it usingread_parquetfrom thenanoparquetpackage rather thanread_csv, like so:tqcs_matched_2010 <- read_parquet("tqcs_matched_detections_2010.parquet")Replace the filename with the appropriate path to your own parquet file. Everything hereafter will work the same:

read_parquetimports the data as a dataframe, and the column names and data types are identical across the CSV and Parquet versions of the detection extract. That means once the data is imported into R, the rest of the code in the workshop will work identically on it.

You may have noticed that our call to read_csv has a second argument: guess_max. This is a useful argument when some of our columns begin with a lot of NULL values. When determining what data type to assign to a column, rather than checking every single entry, R will check the first few and make a guess based on that. If the first few values are null, R will get confused and throw an error when it actually finds data further down in the column. guess_max lets us tell R exactly how many columns to read before trying to make a guess. This way, we know it will read enough entries in each column to actually find data, which it will prioritize over the NULL values when assigning a type to the column. This parameter isn’t always necessary, but it can be vital depending on your dataset.

We can now refer to the variable tqcs_matched_2010 to access, manipulate, and view the data from our CSV. In the next sections, we will explore some of the basic operations you can perform on dataframes.

Exploring Detection Extracts

Let’s start with a practical example. What can we find out about these matched detections? We’ll begin by running the code below, and then give some insight into what each function does. Remember, if you’re ever confused about the purpose of a function, you can use ‘?’ followed by the function name (i.e, ?head, ?View) to get more information.

head(tqcs_matched_2010) #first 6 rows

View(tqcs_matched_2010) #can also click on object in Environment window

str(tqcs_matched_2010) #can see the type of each column (vector)

glimpse(tqcs_matched_2010) #similar to str()

#summary() is a base R function that will spit out some quick stats about a vector (column)

#the $ syntax is the way base R selects columns from a data frame

summary(tqcs_matched_2010$decimalLatitude)

You may now have an idea of what each of those functions does, but we will briefly explain each here.

head takes the dataframe as a parameter and returns the first 6 rows of the dataframe. This is useful if you want to quickly check that a dataframe imported, or that all the columns are there, or see other such at-a-glance information. Its primary utility is that it is much faster to load and review than the entire dataframe, which may be several tens of thousands of rows long. Note that the related function tail will return the last six elements.

If we do want to load the entire dataframe, though, we can use View, which will open the dataframe in its own panel, where we can scroll through it as though it were an Excel file. This is useful for seeking out specific information without having to consult the file itself. Note that for large dataframes, this function can take a long time to execute.

Next are the functions str and glimpse, which do similar but different things. str is short for ‘structure’ and will print out a lot of information about your dataframe, including the number of rows and columns (called ‘observations’ and ‘variables’), the column names, the first four entries of each column, and each column type as well. str can sometimes be a bit overwhelming, so if you want to see a more condensed output, glimpse can be useful. It prints less information, but is cleaner and more compact, which can be desirable.

Finally, we have the summary function, which takes a single column from a dataframe and produces a summary of its basic statistics. You may have noticed the ‘$’ in the summary call- this is how we index a specific column from a dataframe. In this case, we are referring to the latitude column of our dataframe.

Using what you now know about summary functions, try to answer the challenge below.

Detection Extracts Challenge

Question 1: What is the class of the station column in tqcs_matched_2010, and how many rows and columns are in the tqcs_matched_2010 dataset??

Solution

The column is a character, and there are 1,737,597 rows with 36 columns

str(tqcs_matched_2010) # or glimpse(tqcs_matched_2010)

Data Manipulation

Now that we’ve learned how to import and summarize our data, we can learn how to use dplyr to manipulate it. The name ‘dplyr’ may seem esoteric- the ‘d’ is short for ‘dataframe’, and ‘plyr’ is meant to evoke pliers, and thereby cutting, twisting, and shaping. This is an elegant summation of the dplyr library’s functionality.

We are going to introduce a new operator in this section, called the “dplyr pipe”. Not to be confused with |, which is also called a pipe in some other languages, the dplyr pipe is rendered as %>%. A pipe takes the output of the function or contents of the variable on the left and passes them to the function on the right. It is often read as “and then.” If you want to quickly add a pipe, the keybord shortcut CTRL + SHIFT + M will do so.

library(dplyr) #can use tidyverse package dplyr to do exploration on dataframes in a nicer way

# %>% is a "pipe" which allows you to join functions together in sequence.

tqcs_matched_2010 %>% dplyr::select(6) #selects column 6

# Using the above transliteration: "take tqcs_matched_2010 AND THEN select column number 6 from it using the select function in the dplyr library"

You may have noticed another unfamiliar operator above, the double colon (::). This is used to specify the package from which we want to pull a function. Until now, we haven’t needed this, but as your code grows and the number of libraries you’re using increases, it’s likely that multiple functions across several different packages will have the same name (a phenomenon called “overloading”). R has no automatic way of knowing which package contains the function you are referring to, so using double colons lets us specify it explicitly. It’s important to be able to do this, since different functions with the same name often do markedly different things.

Let’s explore a few other examples of how we can use dplyr and pipes to manipulate our dataframe.

tqcs_matched_2010 %>% slice(1:5) #selects rows 1 to 5 in the dplyr way

# Take tqcs_matched_2010 AND THEN slice rows 1 through 5.

#We can also use multiple pipes.

tqcs_matched_2010 %>%

distinct(detectedBy) %>% nrow #number of arrays that detected my fish in dplyr!

# Take tqcs_matched_2010 AND THEN select only the unique entries in the detectedBy column AND THEN count them with nrow.

#We can do the same as above with other columns too.

tqcs_matched_2010 %>%

distinct(catalogNumber) %>%

nrow #number of animals that were detected

# Take tqcs_matched_2010 AND THEN select only the unique entries in the catalogNumber column AND THEN count them with nrow.

#We can use filtering to conditionally select rows as well.

tqcs_matched_2010 %>% filter(catalogNumber=="TQCS-1049258-2008-02-14")

# Take tqcs_matched_2010 AND THEN select only those rows where catalogNumber is equal to the above value.

tqcs_matched_2010 %>% filter(decimalLatitude >= 27.20)

# Take tqcs_matched_2010 AND THEN select only those rows where latitude is greater than or equal to 27.20.

These are all ways to extract a specific subset of our data, but dplyr can also be used to manipulate dataframes to give you even greater insights. We’re now going to use two new functions: group_by, which allows us to group our data by the values of a single column, and summarise (not to be confused with summary above!), which can be used to calculate summary statistics across your grouped variables, and produces a new dataframe containing these values as the output. These functions can be difficult to grasp, so don’t forget to use ?group_by and ?summarise if you get lost.

#get the mean value across a column using GroupBy and Summarize

tqcs_matched_2010 %>% #Take tqcs_matched_2010, AND THEN...

group_by(catalogNumber) %>% #Group the data by catalogNumber- that is, create a group within the dataframe where each group contains all the rows related to a specific catalogNumber. AND THEN...

summarise(MeanLat=mean(decimalLatitude)) #use summarise to add a new column containing the mean decimalLatitude of each group. We named this new column "MeanLat" but you could name it anything

With just a few lines of code, we’ve created a dataframe that contains each of our catalog numbers and the mean latitude at which those fish were detected. dplyr, its wide array of functions, and the powerful pipe operator can let us build out detailed summaries like this one without writing too much code.

Data Manipulation Challenge

Question 1: Find the max lat and max longitude for animal “TQCS-1049258-2008-02-14”.

Solution

tqcs_matched_2010 %>% filter(catalogNumber=="TQCS-1049258-2008-02-14") %>% summarise(MaxLat=max(decimalLatitude), MaxLong=max(decimalLongitude))Question 2: Find the min lat/long of each animal for detections occurring in July.

Solution

tqcs_matched_2010 %>% filter(month(dateCollectedUTC) == 7) group_by(catalogNumber) %>% summarise(MinLat=min(latdecimalLatitudeitude), MinLong=min(decimalLongitude))

Joining Detection Extracts

We’re now going to briefly touch on a few useful dataframe use-cases that aren’t directly related to dplyr, but with which dplyr can help us.

One function that we’ll need to know is rbind, a base R function which lets us combine two R objects together. Since detections for animals tagged during a study often appear in multiple years, this functionality will let us merge the dataframes together. We’ll also use distinct, a dplyr function that lets us trim out duplicate release records for each animal, since these are listed in each detection extract.

tqcs_matched_2011 <- read_csv("tqcs_matched_detections_2011.zip", guess_max = 41881) #Import 2011 detections

tqcs_matched_10_11_full <- rbind(tqcs_matched_2010, tqcs_matched_2011) #Now join the two dataframes

#release records for animals often appear in >1 year, this will remove the duplicates

tqcs_matched_10_11_full <- tqcs_matched_10_11_full %>% distinct() # Use distinct to remove duplicates.

tqcs_matched_10_11 <- tqcs_matched_10_11_full %>% slice(1:110000) # subset our example data to help this workshop run smoother!

tqcs_matched_10_11 <- tqcs_matched_10_11 %>% filter(detectedBy != 'PIRAT.PFRL') #removing erroneous detection in Hawaii

Dealing with Datetimes

Datetime data is in a special format which is neither numeric nor character. It can be tricky to deal with, too, since Excel frequently reformats dates in any file it opens. We also have to concern ourselves with practical matters of time, like time zone and date formatting. Fortunately, the lubridate library gives us a whole host of functionality to manage datetime data. For additional help, the cheat sheet for lubridate may prove a useful resource.

We’ll also use a dplyr function called mutate, which lets us add new columns or change existing ones, while preserving the existing data in the table. Be careful not to confuse this with its sister function transmute, which adds or manipulates columns while dropping existing data. If you’re ever in doubt as to which is which, remember: ?mutate and ?transmute will bring up the help files.

library(lubridate) #Import our Lubridate library.

tqcs_matched_10_11 %>% mutate(dateCollectedUTC=ymd_hms(dateCollectedUTC)) #Use the lubridate function ymd_hms to change the format of the date.

#as.POSIXct(tqcs_matched_10_11$dateCollectedUTC) #this is the base R way - if you ever see this function

We’ve just used a single function, ymd_hms, but with it we’ve been able to completely reformat the entire datecollectedUTC column. ymd_hms is short for Year, Month, Day, Hours, Minutes, and Seconds. For example, at time of writing, it’s 2021-05-14 14:21:40. Other format functions exist too, like dmy_hms, which specifies the day first and year third (i.e, 14-05-2021 14:21:40). Investigate the documentation to find which is right for you.

There are too many useful lubridate functions to cover in the scope of this lesson. These include parse_date_time, which can be used to read in date data in multiple formats, which is useful if you have a column contianing heterogenous date data; as well as with_tz, which lets you make your data sensitive to timezones (including automatic daylight savings time awareness). Dates are a tricky subject, so be sure to investigate lubridate to make sure you find the functions you need.

GLATOS Network

Dataframes and dplyr

In this lesson, we’re going to introduce a package called dplyr. dplyr takes advantage of an operator called a pipe to create chains of data manipulation that produce powerful exploratory summaries. It also provides a suite of further functionality for manipulating dataframes: tabular sets of data that are common in data analysis. If you’ve imported the tidyverse library, as we did during setup and in the last episode, then congratulations: you already have dplyr (along with a host of other useful packages). As an aside, the cheat sheets for dplyr and readr may be useful when reviewing this lesson.

You may not be familiar with dataframes by name, but you may recognize the structure. Dataframes are arranged into rows and columns, not unlike tables in typical spreadsheet format (ex: Excel). In R, they are represented as vectors of vectors: that is, a vector wherein each column is itself a vector. If you are familiar with matrices, or two-dimensional arrays in other languages, the structure of a dataframe will be clear to you.

However, dataframes are not merely vectors - they are a specific type of object with their own functionality, which we will cover in this lesson.

We are going to use GLATOS-style detection extracts for this lesson.

Importing from CSVs

Before we can start analyzing our data, we need to import it into R. Fortunately, we have a function for this. read_csv is a function from the readr package, also included with the tidyverse library. This function can read data from a .csv file into a dataframe. “.csv” is an extension that denotes a Comma-Separated Value file, or a file wherein data is arranged into rows, and entries within rows are delimited by commas. They’re common in data analysis.

For the purposes of this lesson, we will only cover read_csv; however, there is another function, read_excel, which you can use to import excel files. It’s from a different library (readxl) and is outside the scope of this lesson, but worth investigating if you need it.

To import your data from your CSV file, we just need to pass the file path to read_csv, and assign the output to a variable. Note that the file path you give to read_csv will be relative to the working directory you set in the last lesson, so keep that in mind.

#imports file into R. paste the filepath to the unzipped file here!

lamprey_dets <- read_csv("inst_extdata_lamprey_detections.csv", guess_max = 3103)

You may have noticed that our call to read_csv has a second argument: guess_max. This is a useful argument when some of our columns begin with a lot of NULL values. When determining what data type to assign to a column, rather than checking every single entry, R will check the first few and make a guess based on that. If the first few values are null, R will get confused and throw an error when it actually finds data further down in the column. guess_max lets us tell R exactly how many columns to read before trying to make a guess. This way, we know it will read enough entries in each column to actually find data, which it will prioritize over the NULL values when assigning a type to the column. This parameter isn’t always necessary, but it can be vital depending on your dataset.

We can now refer to the variable lamprey_dets to access, manipulate, and view the data from our CSV. In the next sections, we will explore some of the basic operations you can perform on dataframes.

Exploring Detection Extracts

Let’s start with a practical example. What can we find out about these matched detections? We’ll begin by running the code below, and then give some insight into what each function does. Remember, if you’re ever confused about the purpose of a function, you can use ‘?’ followed by the function name (i.e, ?head, ?View) to get more information.

head(lamprey_dets) #first 6 rows

View(lamprey_dets) #can also click on object in Environment window

str(lamprey_dets) #can see the type of each column (vector)

glimpse(lamprey_dets) #similar to str()

#summary() is a base R function that will spit out some quick stats about a vector (column)

#the $ syntax is the way base R selects columns from a data frame

summary(lamprey_dets$release_latitude)

You may now have an idea of what each of those functions does, but we will briefly explain each here.

head takes the dataframe as a parameter and returns the first 6 rows of the dataframe. This is useful if you want to quickly check that a dataframe imported, or that all the columns are there, or see other such at-a-glance information. Its primary utility is that it is much faster to load and review than the entire dataframe, which may be several tens of thousands of rows long. Note that the related function tail will return the last six elements.

If we do want to load the entire dataframe, though, we can use View, which will open the dataframe in its own panel, where we can scroll through it as though it were an Excel file. This is useful for seeking out specific information without having to consult the file itself. Note that for large dataframes, this function can take a long time to execute.

Next are the functions str and glimpse, which do similar but different things. str is short for ‘structure’ and will print out a lot of information about your dataframe, including the number of rows and columns (called ‘observations’ and ‘variables’), the column names, the first four entries of each column, and each column type as well. str can sometimes be a bit overwhelming, so if you want to see a more condensed output, glimpse can be useful. It prints less information, but is cleaner and more compact, which can be desirable.

Finally, we have the summary function, which takes a single column from a dataframe and produces a summary of its basic statistics. You may have noticed the ‘$’ in the summary call- this is how we index a specific column from a dataframe. In this case, we are referring to the latitude column of our dataframe.

Using what you now know about summary functions, try to answer the challenge below.

Detection Extracts Challenge

Question 1: What is the class of the station column in lamprey_dets, and how many rows and columns are in the lamprey_dets dataset??

Solution

The column is a character, and there are 5,923 rows with 30 columns

str(lamprey_dets) # or glimpse(lamprey_dets)

Data Manipulation

Now that we’ve learned how to import and summarize our data, we can learn how to use dplyr to manipulate it. The name ‘dplyr’ may seem esoteric- the ‘d’ is short for ‘dataframe’, and ‘plyr’ is meant to evoke pliers, and thereby cutting, twisting, and shaping. This is an elegant summation of the dplyr library’s functionality.

We are going to introduce a new operator in this section, called the “dplyr pipe”. Not to be confused with |, which is also called a pipe in some other languages, the dplyr pipe is rendered as %>%. A pipe takes the output of the function or contents of the variable on the left and passes them to the function on the right. It is often read as “and then.” If you want to quickly add a pipe, the keybord shortcut CTRL + SHIFT + M will do so.

library(dplyr) #can use tidyverse package dplyr to do exploration on dataframes in a nicer way

# %>% is a "pipe" which allows you to join functions together in sequence.

lamprey_dets %>% dplyr::select(6) #selects column 6

# Using the above transliteration: "take lamprey_dets AND THEN select column number 6 from it using the select function in the dplyr library"

You may have noticed another unfamiliar operator above, the double colon (::). This is used to specify the package from which we want to pull a function. Until now, we haven’t needed this, but as your code grows and the number of libraries you’re using increases, it’s likely that multiple functions across several different packages will have the same name (a phenomenon called “overloading”). R has no automatic way of knowing which package contains the function you are referring to, so using double colons lets us specify it explicitly. It’s important to be able to do this, since different functions with the same name often do markedly different things.

Let’s explore a few other examples of how we can use dplyr and pipes to manipulate our dataframe.

lamprey_dets %>% slice(1:5) #selects rows 1 to 5 in the dplyr way

# Take lamprey_dets AND THEN slice rows 1 through 5.

#We can also use multiple pipes.

lamprey_dets %>%

distinct(glatos_array) %>% nrow #number of arrays that detected my fish in dplyr!

# Take lamprey_dets AND THEN select only the unique entries in the glatos_array column AND THEN count them with nrow.

#We can do the same as above with other columns too.

lamprey_dets %>%

distinct(animal_id) %>%

nrow #number of animals that were detected

# Take lamprey_dets AND THEN select only the unique entries in the animal_id column AND THEN count them with nrow.

#We can use filtering to conditionally select rows as well.

lamprey_dets %>% filter(animal_id=="A69-1601-1363")

# Take lamprey_dets AND THEN select only those rows where animal_id is equal to the above value.

lamprey_dets %>% filter(detection_timestamp_utc >= '2012-06-01 00:00:00') #all dets in/after October of 2016

# Take lamprey_dets AND THEN select only those rows where monthcollected is greater than or equal to June 1 2012.

These are all ways to extract a specific subset of our data, but dplyr can also be used to manipulate dataframes to give you even greater insights. We’re now going to use two new functions: group_by, which allows us to group our data by the values of a single column, and summarise (not to be confused with summary above!), which can be used to calculate summary statistics across your grouped variables, and produces a new dataframe containing these values as the output. These functions can be difficult to grasp, so don’t forget to use ?group_by and ?summarise if you get lost.

#get the mean value across a column using GroupBy and Summarize

lamprey_dets %>% #Take lamprey_dets, AND THEN...

group_by(animal_id) %>% #Group the data by animal_id- that is, create a group within the dataframe where each group contains all the rows related to a specific animal_id. AND THEN...

summarise(MeanLat=mean(deploy_lat)) #use summarise to add a new column containing the mean latitude of each group. We named this new column "MeanLat" but you could name it anything

With just a few lines of code, we’ve created a dataframe that contains each of our catalog numbers and the mean latitude at which those fish were detected. dplyr, its wide array of functions, and the powerful pipe operator can let us build out detailed summaries like this one without writing too much code.

Data Manipulation Challenge

Question 1: Find the max lat and max longitude for animal “A69-1601-1363”.

Solution

lamprey_dets %>% filter(animal_id=="A69-1601-1363") %>% summarise(MaxLat=max(deploy_lat), MaxLong=max(deploy_long))Question 2: Find the min lat/long of each animal for detections occurring in July 2012.

Solution

lamprey_dets %>% filter(detection_timestamp_utc >= "2012-07-01 00:00:00" & detection_timestamp_utc < "2012-08-01 00:00:00" ) %>% group_by(animal_id) %>% summarise(MinLat=min(deploy_lat), MinLong=min(deploy_long))

Joining Detection Extracts

We’re now going to briefly touch on a few useful dataframe use-cases that aren’t directly related to dplyr, but with which dplyr can help us.

One function that we’ll need to know is rbind, a base R function which lets us combine two R objects together. This is particularly useful if you have more than one detection extract provided by GLATOS (perhaps multiple projects).

walleye_dets <- read_csv("inst_extdata_walleye_detections.csv", guess_max = 9595) #Import walleye detections

all_dets <- rbind(lamprey_dets, walleye_dets) #Now join the two dataframes

Dealing with Datetimes

Datetime data is in a special format which is neither numeric nor character. It can be tricky to deal with, too, since Excel frequently reformats dates in any file it opens. We also have to concern ourselves with practical matters of time, like time zone and date formatting. Fortunately, the lubridate library gives us a whole host of functionality to manage datetime data. For additional help, the cheat sheet for lubridate may prove a useful resource.

We’ll also use a dplyr function called mutate, which lets us add new columns or change existing ones, while preserving the existing data in the table. Be careful not to confuse this with its sister function transmute, which adds or manipulates columns while dropping existing data. If you’re ever in doubt as to which is which, remember: ?mutate and ?transmute will bring up the help files.

library(lubridate)

lamprey_dets %>% mutate(detection_timestamp_utc=ymd_hms(detection_timestamp_utc)) #Tells R to treat this column as a date, not number numbers

#as.POSIXct(lamprey_dets$detection_timestamp_utc) #this is the base R way - if you ever see this function

We’ve just used a single function, ymd_hms, but with it we’ve been able to completely reformat the entire detection_timestamp_utc column. ymd_hms is short for Year, Month, Day, Hours, Minutes, and Seconds. For example, at time of writing, it’s 2021-05-14 14:21:40. Other format functions exist too, like dmy_hms, which specifies the day first and year third (i.e, 14-05-2021 14:21:40). Investigate the documentation to find which is right for you.

There are too many useful lubridate functions to cover in the scope of this lesson. These include parse_date_time, which can be used to read in date data in multiple formats, which is useful if you have a column contianing heterogenous date data; as well as with_tz, which lets you make your data sensitive to timezones (including automatic daylight savings time awareness). Dates are a tricky subject, so be sure to investigate lubridate to make sure you find the functions you need.

MigraMar Node

Dataframes and dplyr

In this lesson, we’re going to introduce a package called dplyr. dplyr takes advantage of an operator called a pipe to create chains of data manipulation that produce powerful exploratory summaries. It also provides a suite of further functionality for manipulating dataframes: tabular sets of data that are common in data analysis. If you’ve imported the tidyverse library, as we did during setup and in the last episode, then congratulations: you already have dplyr (along with a host of other useful packages). As an aside, the cheat sheets for dplyr and readr may be useful when reviewing this lesson.

You may not be familiar with dataframes by name, but you may recognize the structure. Dataframes are arranged into rows and columns, not unlike tables in typical spreadsheet format (ex: Excel). In R, they are represented as vectors of vectors: that is, a vector wherein each column is itself a vector. If you are familiar with matrices, or two-dimensional arrays in other languages, the structure of a dataframe will be clear to you.

However, dataframes are not merely vectors- they are a specific type of object with their own functionality, which we will cover in this lesson.

We are going to use OTN-style detection extracts for this lesson. If you’re unfamiliar with detection extracts formats from OTN-style database nodes, see the documentation here

Importing from CSVs

Before we can start analyzing our data, we need to import it into R. Fortunately, we have a function for this. read_csv is a function from the readr package, also included with the tidyverse library. This function can read data from a .csv file into a dataframe. “.csv” is an extension that denotes a Comma-Separated Value file, or a file wherein data is arranged into rows, and entries within rows are delimited by commas. They’re common in data analysis.

For the purposes of this lesson, we will only cover read_csv; however, there is another function, read_excel, which you can use to import excel files. It’s from a different library (readxl) and is outside the scope of this lesson, but worth investigating if you need it.

To import your data from your CSV file, we just need to pass the file path to read_csv, and assign the output to a variable. Note that the file path you give to read_csv will be relative to the working directory you set in the last lesson, so keep that in mind.

#imports file into R. paste the filepath to the unzipped file here!

gmr_matched_2018 <- read_csv("gmr_matched_detections_2018.csv")

Regarding Parquet Files

OTN now sends out detection extracts in

.parquetformat rather than only.csv. Full documentation on the parquet file format can be found here, but in brief, it is an alternative to other tabular data formats that is designed for more efficient data storage and retrieval. If you have a parquet file, you will need to import it usingread_parquetfrom thenanoparquetpackage rather thanread_csv, like so:gmr_matched_2018 <- read_parquet("gmr_matched_2018.parquet")Replace the filename with the appropriate path to your own parquet file. Everything hereafter will work the same:

read_parquetimports the data as a dataframe, and the column names and data types are identical across the CSV and Parquet versions of the detection extract. That means once the data is imported into R, the rest of the code in the workshop will work identically on it.

We can now refer to the variable gmr_matched_2018 to access, manipulate, and view the data from our CSV. In the next sections, we will explore some of the basic operations you can perform on dataframes.

Exploring Detection Extracts

Let’s start with a practical example. What can we find out about these matched detections? We’ll begin by running the code below, and then give some insight into what each function does. Remember, if you’re ever confused about the purpose of a function, you can use ‘?’ followed by the function name (i.e, ?head, ?View) to get more information.

head(gmr_matched_2018) #first 6 rows

view(gmr_matched_2018) #can also click on object in Environment window

str(gmr_matched_2018) #can see the type of each column (vector)

glimpse(gmr_matched_2018) #similar to str()

#summary() is a base R function that will spit out some quick stats about a vector (column)

#the $ syntax is the way base R selects columns from a data frame

summary(gmr_matched_2018$decimalLatitude)

You may now have an idea of what each of those functions does, but we will briefly explain each here.

head takes the dataframe as a parameter and returns the first 6 rows of the dataframe. This is useful if you want to quickly check that a dataframe imported, or that all the columns are there, or see other such at-a-glance information. Its primary utility is that it is much faster to load and review than the entire dataframe, which may be several tens of thousands of rows long. Note that the related function tail will return the last six elements.

If we do want to load the entire dataframe, though, we can use View, which will open the dataframe in its own panel, where we can scroll through it as though it were an Excel file. This is useful for seeking out specific information without having to consult the file itself. Note that for large dataframes, this function can take a long time to execute.

Next are the functions str and glimpse, which do similar but different things. str is short for ‘structure’ and will print out a lot of information about your dataframe, including the number of rows and columns (called ‘observations’ and ‘variables’), the column names, the first four entries of each column, and each column type as well. str can sometimes be a bit overwhelming, so if you want to see a more condensed output, glimpse can be useful. It prints less information, but is cleaner and more compact, which can be desirable.

Finally, we have the summary function, which takes a single column from a dataframe and produces a summary of its basic statistics. You may have noticed the ‘$’ in the summary call- this is how we index a specific column from a dataframe. In this case, we are referring to the latitude column of our dataframe.

Using what you now know about summary functions, try to answer the challenge below.

Detection Extracts Challenge

Question 1: What is the class of the station column in gmr_matched_2018, and how many rows and columns are in the gmr_matched_2018 dataset??

Solution

The column is a character, and there are 2,305 rows with 36 columns

str(gmr_matched_2018) # or glimpse(gmr_matched_2018)

Data Manipulation

Now that we’ve learned how to import and summarize our data, we can learn how to use dplyr to manipulate it. The name ‘dplyr’ may seem esoteric- the ‘d’ is short for ‘dataframe’, and ‘plyr’ is meant to evoke pliers, and thereby cutting, twisting, and shaping. This is an elegant summation of the dplyr library’s functionality.

We are going to introduce a new operator in this section, called the “dplyr pipe”. Not to be confused with |, which is also called a pipe in some other languages, the dplyr pipe is rendered as %>%. A pipe takes the output of the function or contents of the variable on the left and passes them to the function on the right. It is often read as “and then.” If you want to quickly add a pipe, the keybord shortcut CTRL + SHIFT + M will do so.

library(dplyr) #can use tidyverse package dplyr to do exploration on dataframes in a nicer way

# %>% is a "pipe" which allows you to join functions together in sequence.

gmr_matched_2018 %>% dplyr::select(6) #selects column 6

# Using the above transliteration: "take gmr_matched_2018 AND THEN select column number 6 from it using the select function in the dplyr library"

You may have noticed another unfamiliar operator above, the double colon (::). This is used to specify the package from which we want to pull a function. Until now, we haven’t needed this, but as your code grows and the number of libraries you’re using increases, it’s likely that multiple functions across several different packages will have the same name (a phenomenon called “overloading”). R has no automatic way of knowing which package contains the function you are referring to, so using double colons lets us specify it explicitly. It’s important to be able to do this, since different functions with the same name often do markedly different things.

Let’s explore a few other examples of how we can use dplyr and pipes to manipulate our dataframe.

gmr_matched_2018 %>% slice(1:5) #selects rows 1 to 5 in the dplyr way

# Take gmr_matched_2018 AND THEN slice rows 1 through 5.

#We can also use multiple pipes.

gmr_matched_2018 %>%

distinct(detectedBy) %>%

nrow #number of arrays that detected my fish in dplyr!

# Take gmr_matched_2018 AND THEN select only the unique entries in the detectedBy column AND THEN count them with nrow.

#We can do the same as above with other columns too.

gmr_matched_2018 %>%

distinct(catalogNumber) %>%

nrow #number of animals that were detected

# Take gmr_matched_2018 AND THEN select only the unique entries in the catalogNumber column AND THEN count them with nrow.

#We can use filtering to conditionally select rows as well.

gmr_matched_2018 %>% dplyr::filter(catalogNumber=="GMR-25718-2014-01-17")

# Take gmr_matched_2018 AND THEN select only those rows where catalogNumber is equal to the above value.

gmr_matched_2018 %>% dplyr::filter(decimalLatitude >= 0)

# Take gmr_matched_2018 AND THEN select only those rows where latitude is greater than or equal to 0.

These are all ways to extract a specific subset of our data, but dplyr can also be used to manipulate dataframes to give you even greater insights. We’re now going to use two new functions: group_by, which allows us to group our data by the values of a single column, and summarise (not to be confused with summary above!), which can be used to calculate summary statistics across your grouped variables, and produces a new dataframe containing these values as the output. These functions can be difficult to grasp, so don’t forget to use ?group_by and ?summarise if you get lost.

#get the mean value across a column using GroupBy and Summarize

gmr_matched_2018 %>% #Take gmr_matched_2018, AND THEN...

group_by(catalogNumber) %>% #Group the data by catalogNumber- that is, create a group within the dataframe where each group contains all the rows related to a specific catalogNumber. AND THEN...

summarise(MeanLat=mean(decimalLatitude)) #use summarise to add a new column containing the mean decimalLatitude of each group. We named this new column "MeanLat" but you could name it anything

With just a few lines of code, we’ve created a dataframe that contains each of our catalog numbers and the mean latitude at which those fish were detected. dplyr, its wide array of functions, and the powerful pipe operator can let us build out detailed summaries like this one without writing too much code.

Data Manipulation Challenge

Question 1: Find the max lat and max longitude for animal “GMR-25720-2014-01-18”.

Solution

gmr_matched_2018 %>% dplyr::filter(catalogNumber=="GMR-25720-2014-01-18") %>% summarise(MaxLat=max(decimalLatitude), MaxLong=max(decimalLongitude)Question 2: Find the min lat/long of each animal for detections occurring in/after April.

Solution

gmr_matched_2018 %>% filter(monthcollected >= 4 ) %>% group_by(catalogNumber) %>% summarise(MinLat=min(decimalLatitude), MinLong=min(longitdecimalLongitudeude))

Joining Detection Extracts

We’re now going to briefly touch on a few useful dataframe use-cases that aren’t directly related to dplyr, but with which dplyr can help us.

One function that we’ll need to know is rbind, a base R function which lets us combine two R objects together. Since detections for animals tagged during a study often appear in multiple years, this functionality will let us merge the dataframes together. We’ll also use distinct, a dplyr function that lets us trim out duplicate release records for each animal, since these are listed in each detection extract.

gmr_matched_2019 <- read_csv("gmr_matched_detections_2019.csv") #First, read in our file.

gmr_matched_18_19 <- rbind(gmr_matched_2018, gmr_matched_2019) #Now join the two dataframes

# release records for animals often appear in >1 year, this will remove the duplicates

gmr_matched_18_19 <- gmr_matched_18_19 %>% distinct() # Use distinct to remove duplicates.

view(gmr_matched_18_19)

Dealing with Datetimes

Datetime data is in a special format which is neither numeric nor character. It can be tricky to deal with, too, since Excel frequently reformats dates in any file it opens. We also have to concern ourselves with practical matters of time, like time zone and date formatting. Fortunately, the lubridate library gives us a whole host of functionality to manage datetime data. For additional help, the cheat sheet for lubridate may prove a useful resource.

We’ll also use a dplyr function called mutate, which lets us add new columns or change existing ones, while preserving the existing data in the table. Be careful not to confuse this with its sister function transmute, which adds or manipulates columns while dropping existing data. If you’re ever in doubt as to which is which, remember: ?mutate and ?transmute will bring up the help files.

library(lubridate) #Import our Lubridate library.

gmr_matched_18_19 %>% mutate(dateCollectedUTC=ymd_hms(dateCollectedUTC)) #Use the lubridate function ymd_hms to change the format of the date.

#as.POSIXct(gmr_matched_18_19$dateCollectedUTC) #this is the base R way - if you ever see this function

We’ve just used a single function, ymd_hms, but with it we’ve been able to completely reformat the entire datecollectedUTC column. ymd_hms is short for Year, Month, Day, Hours, Minutes, and Seconds. For example, at time of writing, it’s 2021-05-14 14:21:40. Other format functions exist too, like dmy_hms, which specifies the day first and year third (i.e, 14-05-2021 14:21:40). Investigate the documentation to find which is right for you.

There are too many useful lubridate functions to cover in the scope of this lesson. These include parse_date_time, which can be used to read in date data in multiple formats, which is useful if you have a column contianing heterogenous date data; as well as with_tz, which lets you make your data sensitive to timezones (including automatic daylight savings time awareness). Dates are a tricky subject, so be sure to investigate lubridate to make sure you find the functions you need.

OTN Node

Dataframes and dplyr